|

|

|

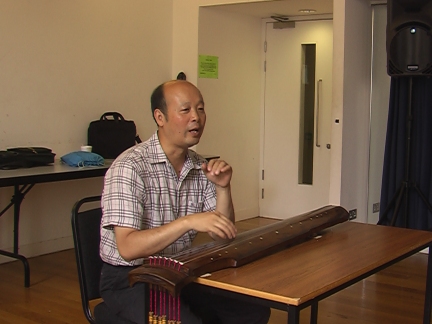

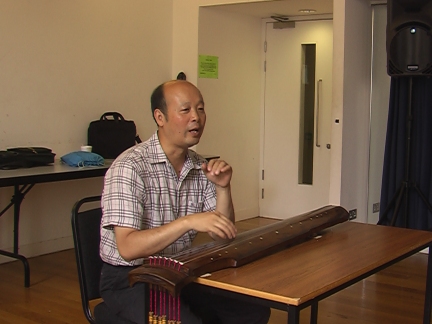

| Zeng Chengwei discussing Gu Guan Yu Shen |

Charlie Huang playing Xiang Fei Yuan | Joshua

Petkovic

playing Jiu

Kuang |

Copyright the London Youlan Qin Society, 2008. All

rights reserved.

This, the 33rd

meeting of the London Youlan Qin

Society, was held at the Royal Aademy of Music in London, during the

Chinese Music Summer School.

This, the 33rd

meeting of the London Youlan Qin

Society, was held at the Royal Aademy of Music in London, during the

Chinese Music Summer School. |

|

|

| Zeng Chengwei discussing Gu Guan Yu Shen |

Charlie Huang playing Xiang Fei Yuan | Joshua

Petkovic

playing Jiu

Kuang |

Copyright the London Youlan Qin Society, 2008. All

rights reserved.