Beijing

alone there are 29 schools specialising in teaching qin. In

Shanghai there are 5 or 6 similar organisations which aim at

popularising qin music. In

Kunming there are three qin schools

on one

street alone. There is one person who spends half of his week in

Tianjin; the other half of the week he spends in Beijing. He teaches qin

in both places. There is one person, a Mr Mao, who teaches in

Nanjing,

Beijing, Suzhou and Shanghai. So we pull his leg and ask him how anyone

can have the energy to do so much! There are two guqin societies at

Nanjing University. There is one at Beijing University, but it has 400

or 500 members who are enthusiastic about qin. In the foreign languages

schools in Beijing there are 40-50 people who want to learn the qin.

Not long ago I received a letter inviting me to be the

guqin consultant at a

university in Guangdong. I had never even heard

of the university, let alone the society. There is a national

university in Hefei, the Chinese University of Science an Technology,

where I have given three lectures. The first was for the

leadership, the second for senior staff, the third for students. Since

these three lectures, guqin music

has become much more popular in Hefei

and there are now concerts and public demonstrations. There is now one

guqin school in Shanghai

which has 600-700 students. Small guqin

concerts can be heard at more or less any time. Theree are

places in

Shanghai where they opened a "guqin room";

on the door they put "the

owner is a student of Gong Yi". Suddenly everything looks wonderful.

That's one aspect.

Beijing

alone there are 29 schools specialising in teaching qin. In

Shanghai there are 5 or 6 similar organisations which aim at

popularising qin music. In

Kunming there are three qin schools

on one

street alone. There is one person who spends half of his week in

Tianjin; the other half of the week he spends in Beijing. He teaches qin

in both places. There is one person, a Mr Mao, who teaches in

Nanjing,

Beijing, Suzhou and Shanghai. So we pull his leg and ask him how anyone

can have the energy to do so much! There are two guqin societies at

Nanjing University. There is one at Beijing University, but it has 400

or 500 members who are enthusiastic about qin. In the foreign languages

schools in Beijing there are 40-50 people who want to learn the qin.

Not long ago I received a letter inviting me to be the

guqin consultant at a

university in Guangdong. I had never even heard

of the university, let alone the society. There is a national

university in Hefei, the Chinese University of Science an Technology,

where I have given three lectures. The first was for the

leadership, the second for senior staff, the third for students. Since

these three lectures, guqin music

has become much more popular in Hefei

and there are now concerts and public demonstrations. There is now one

guqin school in Shanghai

which has 600-700 students. Small guqin

concerts can be heard at more or less any time. Theree are

places in

Shanghai where they opened a "guqin room";

on the door they put "the

owner is a student of Gong Yi". Suddenly everything looks wonderful.

That's one aspect.  |

|

|

| Zhao Xiaomei playing Yi Guren |

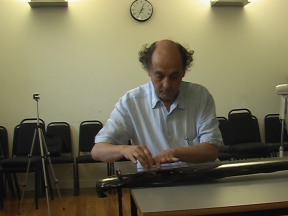

Gong

Yi playing Da Hujia |

Christopher

Evans playing Shen Ren Chang |

Copyright the London Youlan Qin Society, 2006. All

rights reserved.