As there were a number of new

people, not all of whom were familiar with the qin, Cheng Yu gave a

short an introductory talk. She explained the importance of the qin

within Chinese culture and beyond, citing its designation by

UNESCO in

2003 as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

She also announced the designation by by the Chinese government of an

annual Cultural Heritage day on the second Saturday of every June. On

that day in China and overseas there will be many qin-related activities, and we will

arrange our next yaji to

coincide with it as closely as possible. She went on to describe the

London Youlan Qin Society's

activities since its formation in 2003 and the annual Chinese Music

Summer Schools.

As there were a number of new

people, not all of whom were familiar with the qin, Cheng Yu gave a

short an introductory talk. She explained the importance of the qin

within Chinese culture and beyond, citing its designation by

UNESCO in

2003 as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

She also announced the designation by by the Chinese government of an

annual Cultural Heritage day on the second Saturday of every June. On

that day in China and overseas there will be many qin-related activities, and we will

arrange our next yaji to

coincide with it as closely as possible. She went on to describe the

London Youlan Qin Society's

activities since its formation in 2003 and the annual Chinese Music

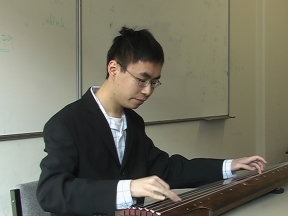

Summer Schools.  Meihua San Nong 梅花三弄

(Three Variations on the Plum Blossom), Guangling version, played by Chen

Jinwei. The rhythm of this version is different to the "traditional"

version, and is more syncopated.

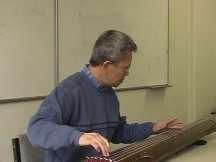

Meihua San Nong 梅花三弄

(Three Variations on the Plum Blossom), Guangling version, played by Chen

Jinwei. The rhythm of this version is different to the "traditional"

version, and is more syncopated.

|

|

|

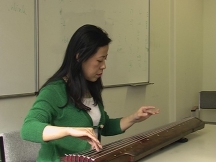

| Cheng Yu, played Shen Ren Chang |

Charlie

Huang, played Liu Shui |

Zhu Wencheng, played Meihua San Nong |

Copyright the London Youlan Qin Society, 2006. All

rights reserved.