2nd October 2005

This, the 16th meeting of the London Youlan Qin

Society, was held at the home of Sarah Moyse in southwest London.

Programme

- John Thompson: Evening

Melodies for the Silk String Zither; Jiu Kuang* - see below

- Charlie Huang: Gao Shan*

- Dan Nung Ing: Ping Sha Luo Yan#

- Christopher Evans: Jiu Kuang^

- Julian Joseph: Ping Sha Luo

Yan^

- Marnix Wells: Guanshan

Yue*

* Played on a qin made

by Wang Peng with

silk strings

# Played on a Qing Dynasty qin ca. 200 years old with

silk strings

^ Played on a qin made

by Zeng Chengwei with

steel/nylon strings

Introduction

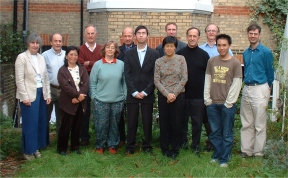

We were pleased to welcome qin researcher

and player John Thompson from New York.

Evening Melodies for the Silk String Zither

A qin recital by John

Thompson

The following pieces were to be played at an evening recital in a

church later in the week as part of the Tartu Early Music Festival.

All have a theme related to evening. Although it was not evening in

London when John played these pieces for us... it was late evening in

China, which was perhaps more to the point!

Each title links to more detailed information about the piece on John's

web site, from which much of what follows is quoted or adapted.

- Guanghan Qiu (Autumn in a Lunar

Palace) (Shenqi Mipu,

1425)

Guanghan (broad, cold)

refers to the moon. The original preface says: "During the clear autumn

season, nights are

cool and people are tranquil; the heavens are vast and bright, the moon

ascends gloriously, and the moon [goddess] is beautiful. A pure

fragrance spreads throughout the universe, and red cassias seem to

float around in the Heavens. This piece has the joy of wandering

to and fro while doing what one wants. How could a commonplace person

achieve or understand this? So these interests are best expressed on

the qin. Only people who eat

the wind and drink the dew can attain

this".

- Tian Feng Huan Pei (Jade Pendants

in a Heavenly Breeze) (Shenqi Mipu,

1425)

The original preface says: "

The predisposition of this piece is like a white moon on a pleasantly

cool evening. The clouds are light and few stars can be seen, the

cornelian jade tinkles in the wind, and

there is a lot of jade-like dew. Floating like a spirit wandering in

the heavens, the immortal wanders in the darkened

universe. Some jade clinks and other jade tinkles.

Nobody can be seen, one just hears the sounds of jingling jade, causing

those who hear it to be able to bring up thoughts

of immortals, and ideas of becoming an immortal.

If one is not among spirits and immortals, how can one have knowledge

of this?"

- Wu Ye Ti (Evening Call of the Raven)

(Shenqi Mipu, 1425)

This piece was reconstructed during the 1950's,

and

has since then become a popular part of the modern repertoire. It

concerns a specific event in the 5th century: prince Liu

Yikang was banished from the capital because of a supposed offence

against his brother the king. He and his nephew cried about the

situation. When the king heard about this, he summoned him back to the

capital, causing him great fear. However the evening before he was due

to return to the capital, some women in his household heard a raven

calling. Such a call was considered lucky, and sure enough he was

forgiven and restored to his former rank.

- Feng Ru Song Ge (Song of Wind

through the Pines) (Taigu Yiyin, 1511) - qin song

Taigu Yiyin (1511) says the melody was written by Ji Kang, but

does not identify the source of the lyrics. The lyrics translated below

are

included in Yuefu Shiji, and are said to be by the Tang Dynasty

monk Jiaoran:

In the

Western mountains the pines have sounds in the

setting sun of autumn, 1,000 branches and 10,000 leaves in the wind

sough.

A wonderful

person takes his qin

and

his playing forms a song, creating amongst the pines sounds both brief

and long.

Sounds brief

and long clear my spirit; one need only mention (such melodies as)

Flowing Waves and

Ruined Mounds.

The wonderful

person at night sits under the bright moon, with little discourse plays

clear tones.

The breeze:

how cool; whirling and fluttering, stirring up the cool pine trees, and

night arrives.

At night

before midnight the tune is so long, (moving on the) qin top in

an even

greater hurry as the sound becomes agitated.

What person at

this time would not be thoughtful, with such bitter

feelings and sad notes heard in the guest hall?

John played this first as an instrumental solo, and then sang it with qin

accompaniment.

- Zui Weng Yin (Old Toper's Chant)

(Two versions: Fengxuan Xuanpin, 1539 and Longmu Qinpu, 1571) - qin song

John played the two versions first as instrumental solos, and then sang

them with qin accompaniment. He originally thought the later

version would be

the harder to sing, but found in practice it worked fairly well. Where qin

tablatures have lyrics, he finds there is usually no

indication as to how

the words relate to music. Usually, he assumes one character per

right-hand stroke, and one per left hand pluck or slide. He uses the

rhythms suggested by the fingerings, which in this case is much the

same

for both versions.

- Mei Shao Yue (Moon Atop a Plum Tree)

(Xilutang Qintong, 1549)

This melody survives only in Xilutang Qintong (1549),

which says it was inspired by the reclusive Song dynasty poet Lin Bu

(967-1028). A

lifelong resident of Hangzhou, Lin spent 20 years as a recluse on

Orphan Mountain, an island in Hangzhou's West Lake. He never married,

claiming that he considered plum trees his wife and pet

cranes his children. The preface in Xilutang Qintong

compares the beauty of the

melody to the beauty of a line in Lin Bu's poem "Small Plum Tree in my

Mountain Garden", which has been translated as

follows:

When

everything has faded they alone shine forth, encroaching on the

charms of smaller gardens.

Their scattered

shadows fall lightly on clear water, their subtle scent

pervades the moonlit dusk.

Snowbirds look

again before they land, butterflies would

faint if they but knew.

Thankfully I can

flirt in whispered verse, I don't need a

sounding board or winecup.

- Zui Yu Chang Wan (A Drunken

Fisherman Sings in the Evening) (Xilutang Qintong, 1549)

This early version is musically unrelated to the melody of this

title played today, the first occurrence of which was not until Tianwenge

Qinpu of 1876, which attributes it to the Sichuan qin player Zhang

Kongshan.

- Zhong Qiu Yue (Mid Autumn Moon)

(Songxianguan Qinpu, 1614)

This piece exists only in this one handbook, which contains no

prefaces.

- Qiu Jiang Ye Bo (Autumn River

Night Anchorage) (Songxianguan Qinpu, 1614)

The melodies in Feng Xuan Xuan Pin

are said to be as played by Yan Tianchi, founder of the Yushan School.

Three titles appear in it for the first time. One of these is Qiu

Jiang Ye Bo, which is actually very similar to Yin De (Hidden Virtue) in Shenqi Mipu. According to Yushan

School tradition, Yan Tianchi was playing qin within earshot of of Maple

Bridge and the nearby Chan (Zen) temple bell. Inspired by a poem of the

same title, he extemporised this piece. Yin De exists in several earlier

handbooks but always in the same version, which suggests that people

must have been playing it strictly from scores. John believes Yan Tianchi must have changed it

sufficiently as he played that it became a new piece.

- Liang Xiao Yin (Peaceful Evening

Prelude) (Songxianguan Qinpu, 1614)

Liang Xiao Yin is still in

the active repertoire. This is the earliest occurrence of the piece

under this title.

- Jiu Kuang

(Yang Lun Taigu Yiyin, 1609)

This version has lyrics, an English translation of the first verse of

which is given below. John sang the Chinese and English versions. One

of the reasons he does not think Jiu

Kuang has triple rhythm is that

these lyrics do not seem to fit when triple rhythm is used.

Fleet

worldly matters: I laugh at the

strain. Quiet, sad feelings

are wasted pain.

How to cure

sadness: call for wine! When drunk all day bad manners are

fine.

Each day of my

whole life through, I should drink great pots of brew.

It is such

bliss, to cruise the Land of Booze;

Sober, then

drunk; drunk and wild as I choose.

Once in the

hills I forget big news.

This piece was not played as a part of the evening theme, but to try

out Dan Nung's recently repaired Qing Dynasty qin.

Questions and answers

Q: How do you go about determining rhythm?

A: I look for structures and repeated patterns. It's more

straightforward for songs, where I try to fit the rhythm of the melody

to a possible rhythm of the lyrics. I start by reading through through

the tablature and putting in whole notes, looking for repeating

patterns. These may be variations, as in some passages in Qiu Jiang

Ye Bo. In this piece, pairs of structures, like a question and

answer, are common. It usually ends up fairly "4-square", and then

becomes

more free. Like most Chinese music, qin music is in double

rhythm, but is played in a more free manner.

Q: Did any of these tunes originate from folk songs?

A: It's hard to tell the origin of melodies. The official

position is yes. The Yuefu Shiji is said to be a collection of

old

melodies, and contains many song texts. A common belief about qin

music is that originally, the music used predomionantly right hand

techniques. Guangling San is a very early piece, and it does

use a

lot of right hand techniques and harmonics. But You Lan,

documented

from the 6th century, uses many left hand techniques, so qins

must have

had a smooth playing surface by then.

Q: Do Zhou Dynasty qins show signs of wear where they

were

rubbed by the left hand?

A: I don't know. Bo Lawergren's research has led him to think

that the qin originated from instruments found in 3rd-5th

century

tombs in south China. He has written articles showing how they have

become longer and narrower, and thus more qin-like. These early

qins

had about 10 strings, reducing to 7. However Chinese tradition says

that qins started with 5 strings, and 2 were added later.

Perhaps the qin developed from a 5-stringed northern instrument

which has

not

survived in tombs. The northern soil is said not to be conducive to the

preservation of wooden objects.

|

|

|

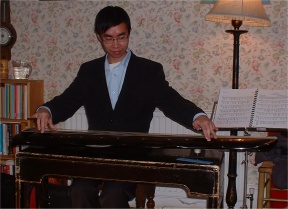

Charlie Huang plays Gao Shan

|

Brian Cox

plays Tao Yuan

|

Dan Nung

Ing

plays Ping Sha Luo Yan |

Copyright the London Youlan Qin Society,

2005. All

rights reserved.