Shi Tan Zhang 释谈章 and Puan Zhou 普庵咒

By Chan Chong Hin 陈松宪

June, 1992

Introduction

Puan Zhou 普庵咒 is

one of the widely known, traditional qin pieces which

have been handed down to the present time. Most qin

handbooks call it Shi Tan Zhang 释谈章. Are these

two pieces in fact one and the

same piece with different titles, or two completely different pieces?

It seems

that until now no one has investigated this question in depth.

Two years ago, the author

had the good fortune to meet Rong Size 容思泽 in Hong Kong and to hear him

play Shi Tan Zhang. The mood and the

music were ancient and simple, grave and stern, solemn and respectful,

far

surpassing the Puan Zhou usually

heard. Since then this refined tune has frequently lingered in my mind.

Later,

I found out from Qin Ren Wen Xun Lu 琴人问讯录 in Jinyu Qinkan 今虞琴刊, Jindai Qinren Lu

近代琴人录 in Qin Fu 琴府 and other sources

that there seem to be very few people who can play Shi Tan

Zhang - apparently only the school to which Mr. Rong

belongs. Nonetheless I feel it is a great treasure.

Last year, Mr. Rong gave me

a recording of himself playing several pieces on the qin.

Among these was Shi Tan

Zhang. So, based on Mr. Rong's recording and a phrase by phrase

comparison

with the qin score of Shi Tan Zhang

in Qin Se He Pu 琴瑟合谱, which

was edited by his great grandfather Qing Rui 庆瑞, I played it phrase by

phrase in the correct order, until eventually I had mastered the entire

piece.

I used cipher notation as a convenient means of recording what I had

learned.

Besides learning the piece, I have analysed and compared Shi

Tan Zhang and Puan Zhou

and written a short report.

Shi Tan Zhang

Shi Tan Zhang first appeared in the late Ming (Wanli

万历 period) qin handbook

San Jiao Tong Sheng 三教同声, edited

by Zhang Dexin 张德新 in 1592.

This collection of scores contains only four

pieces:

1.

Ming De

Yin 明德引

2.

Kong

Sheng Jing 孔圣经

3.

Qing

Jing Jing 清静经

4.

Shi

Tan Zhang 释谈章

Hence the name San Jiao Tong

Sheng[1]

Since I do not have this

material available for reference, I have no details of their content.

Later

collections of scores containing this piece are numerous:

Late Ming:

·

1609 – Yang

Lun's 杨§抡 Bo Ya Xin Fa 伯牙心法

·

1611 – Zhang

Daming's 张大名大命 Yang Chun Tang Qinpu 阳春堂琴谱

·

1625 – Chen

Dabin's 陈大斌

Tai Yin Xi Sheng 太音希声

·

1634 – Zhu

Changfang's 朱常汸 Gu Yin Zheng Zong 古音正宗

·

1634 – Tao

Hongkui's 陶鸿逵 Tao Shi Qinpu 陶氏琴谱

(The

above are in Qinqu Jicheng 琴曲集成 volumes 7

and 9)

Qing 清:

·

1802 – Wu

Hong's 吴灴 Zi Yuan

Tang Qinpu 自远堂琴谱

·

1864 – Zhang

He's 张鹤 Qin Xue Rumen 琴学入门

·

1870 – Qing

Rui's 庆瑞 Qin Se He Pu 琴瑟合谱

(The

above are in volume 1 of Qin Fu 琴府).

In addition,

it is recorded that most of the wealth of famous qin

score collections published during the Qing Dynasty contain

this piece, but as I do not have these materials, I cannot list them

individually.

The

division into sections varies among the above scores of Shi

Tan Zhang. For example: Fo

Tou 佛头, Qi Zhou 起咒, 3

cycles and 15 zhuan plus Fo Wei 佛尾;

21 sections; 8 sections; 5

sections; there are even some that are not divided into sections at

all. But

structurally they are all the same: all are as in Qin Se

He Pu, which is divisible into Fo Zhou Tou 佛咒头, Qi Zhou,

First Cycle (6 sections), Second Cycle (6 sections), Third

Cycle (6 sections) and Fo Zhou Wei 佛咒尾, a total

of 21 sections.

Furthermore,

all scores except Qin Se He Pu have words

alongside [the music notation]. From the words we can see that it is a

Buddhist

scripture. Taking the Shi Tan Zhang

in Qin Se He Pu as a base, and

referring to the text in the Zi Yuan Tang

Qinpu and Qinxue Rumen, we can

now analyse the entire piece as follows:

The

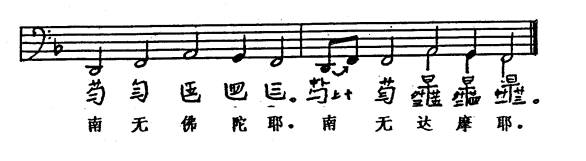

words to Fo Zhou Tou are as follows:

Nan mo fo tuo ye. Nan mo da mo ye... Nan wu

bai wan huo shou jin gang wang pu sa 南无佛陀耶。南无达摩耶。. . . 南无百万火首金刚王菩萨。(In some qin handbooks, we have the

additional words Nan wu Puan Chan shi pu sa, mo he sa 南无普庵禅师菩萨,摩诃萨), which seem to be repeated

or omitted). This section is a hymn praising the name of every Buddha.

The

music has only 7 phrases, and the whole seems to be a simple repeated

theme, as

in example 1 below:

Example 1 Fo Zhou Tou

The

words of the second section, Qi Zhou,

are:

An. Jia jia jia yan jie. Zhe zhe zhe shen

re ... 唵。迦迦迦妍界。遮遮遮神惹.

According to research carried out by Wang Weishi 王微士 of Taiwan, these

are Chinese interpretations of Sanskrit initials and consonants. Table

1

(below) shows a comparison of the syllables in Pinyin and Chinese

characters:

|

Glottals |

迦 ka |

迦 kha |

迦 ga |

妍 gha |

界 na |

|

Palatals |

遮 ca |

遮 cha |

遮 ja |

神 jha |

惹 na |

|

Linguals |

吒 ta |

吒 tha |

吒 da |

怛dha |

那 na |

|

Dentals |

多 ta |

多 tha |

多 da |

檀 dha |

那 na |

|

Labials |

波 pa |

波 pha |

波 ba |

梵 bha |

摩 ma |

Table 1 The Sanskrit syllables and their Chinese

interpretations

In the

Buddhist scripture there is an oral tradition for learning the sounds

of

Sanskrit. It is called Xi Tan Zhang 悉昙章 (the Tao

Shi Qinpu Ì陶氏琴谱 uses this as the title for the

piece). Could Shi Tan 释谈 be

variant characters for Xi Tan 悉昙? We must seek

evidence from

scholars with experience in the study of Buddhism. From the text of Shi Tan Zhang, however, it would seem

that the notion that it is a tune for learning Sanskrit pronunciation

must be

correct.

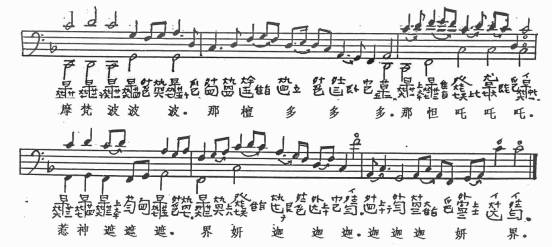

In Qi Zhou, the syllables

are chanted both

in the order shown in the Table 1 and in the opposite order, and on

this basis

is divisible into two parts. The first part is sung in the order shown

in the

table: glottals – palatals – linguals – dentals – labials. The music is

also

very simple, being made up of only a single repeated phrase (see score

example

2). The second half of Qi Zhou is a

chant in which the syllables are chanted in the opposite order. In this

part

the Sanskrit text and the music are also very regularised (score

example 3).

Furthermore the 6th section of each of cycles

1, 2 and 3 is repeated as shown in examples 2 and 3 below:

Example 2 Qi Zhou, first part

Example 3 Qi Zhou, second part

Cycles 1,

2 and 3 are each divided into 6 short sections. The 6th section of each of these is the repeated

part of Qi Zhou (score example 3).

Sections 1-5 of each cycle consist of the sounds of Sanskrit initial

consonants

and vowels (single or compound) (a, i, u, ai, e) put together to form

the

chanted syllables. The five sections in each of these three cycles are

in order

of the initial consonants: glottals, palatals, linguals, dentals and

labials.

Apart from the insertion of half-vowels and nasal sounds, and

fluctuation by

several beats, the music in the 15 sections of these three cycles is

all

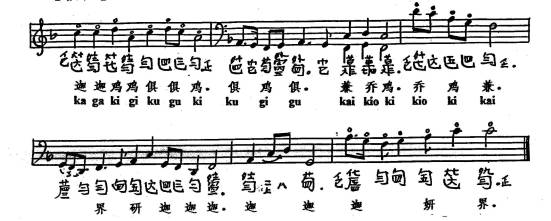

derived from performance variations of a single melody. The first

section of

cycle 1 is shown in example 4:

Example 4 Cycle 1, section 1

The

last section, Fo Zhou Wei, is played

in harmonics and summarises the whole piece. The words are: An.

Bo duo zha. Zhe jia ye. Ye lan ke.

....... Puan dao ci. Bai wu jin ji. 唵。波多吒。遮迦

耶。夜兰诃。 ...普庵到此。百无

禁

忌。 The text of this section very probably

comprises the essentials of

an incantation by the Buddhist priest Puan 普庵. The title Puan

Zhou may derive from

this (early qin handbooks, such as Bo Ya

Xin Fa etc. already contained a note to the effect that

Shi Tan Zhang is Puan Zhou). The

Buddhist priest Puan was the Southern Song high

priest Yin Su 印肃 (AD 1115–69). He went to

Mt. Nan Quan 南泉山, Yuanzhou 袁州 to spread the word of Buddhism; the

occasion was the

grandest the country

had ever seen. It is said that Shi Tan

Zhang was a song used by this Chan 禅

priest to teach his

disciples

Sanskrit pronunciation.

Shi Tan Zhang appears to be too old to be

traced it from its origin to the time of the priest Puan, in the

twelfth

century. However, none of the qin

study materials from the entire 400 years up to the beginning of the

Ming

Dynasty mention these pieces. Since most qin

players of the period had Taoist leanings, it is possible that they

excluded

Buddhist pieces. However this piece is not mentioned in the Qin

Shu Da Quan 琴书大全 (1590),

which contains some stories about Buddhist monks who were qin

players, so that is not very likely.

According

to the annotations to Shi Tan Zhang

in Taiyin Xisheng 太音希声, edited

by Chen Dabin 陈大斌 (1625),

"This piece was composed by Li Shuinan 李水南; before that this music did

not exist. It was

because Lü Xuanjun 吕选君

of Xizhou 希周 in Chongde 崇德 had a taste for Buddhism and Taoism. He

asked

Shuinan to write this music according to the temperament, but it was

not disseminated.

I learned it [from Shuinan] quite a long time ago. Only after I played

it for

the relief of victims of a calamity in the year Wuyin 戊

寅 of the Wanli 万历 period (1578) did it spread widely.

...". If what Chen Dabin said is

correct, then it is a composition by Li Shuinan of the Zhe

浙 school, and it must date from the end of the 16th century.

Shi Tan Zhang was composed according to

the sound (声): one character to one note, with the

rhythmic pattern quite

strictly defined. This gives it a very different flavour from normal qin pieces, which have a flexible tempo

(节奏). According to what is recorded in

all qin handbooks, the melodies are all the same even

though the hui positions are different. For the

most part, the Ming handbooks repeat [the same music] section for

section,

phrase for phrase; those of the Qing Dynasty show numerous performance

changes.

Taking the Qin Se He Pu as an

example, its every repeated phrase or musical section shows some

variation. It

contrasts each different register (音区),

and uses the interplay between the

open, stopped and harmonic timbres, so that within the 21 sections,

each phrase

shows changes and each section shows differences. Not only does it not

make the

listener feel it is a rigid and inflexible monophony, it lingers in the

mind

for a long time. It is a solemn and respectful, grave and stern

artistic

conception.

2. Puan

Zhou

In

addition to Shi Tan Zhang, the Zi Yuan

Tang Qinpu contains piece called Puan Zhou. It has

13 sections and

some religious text is appended to it. By analysing this text we can

see that

it is derived from Shi Tan Zhang,

but:

·

it omits Fo Zhou Tou

·

it omits the

first part of Qi Zhou and, from each cycle, the

chanting of those syllables which have palatal and dental initials

·

the latter

part of Qi Zhou is retained without modification

and is inserted between each of the cycles

·

Fo

Zhou Wei is reduced to a

phrase in harmonics which concludes the piece (see

Table 2)

Apart from the omission of certain

sections and the addition of some open string notes and ornaments, the

melodic

line closely resembles Shi Tan Zhang.

One can state categorically that the 13 section Puan Zhou

is an abridged version of Shi Tan Zhang.

Beside the qin piece Puan Zhou, it has also been handed down as a folk

instrumental

piece. In Xian Suo Bei Kao 弦索备考, published in 1814 by

Rong 荣斋 of the Qing Dynasty, there is a score

for an ensemble version of Puan Zhou

with parts for erhu, pipa, sanxian and zheng. There

is a note at the beginning of the score which says that "Puan

Zhou is the qin piece Shi Tan Zhang."

A pipa piece of the same name was

published in 1818 in the Hua Qiuping

Pipapu »ª 华秋萍琵琶谱 and Ju

Shilin Pipapu 鞠士林琵琶谱.

Furthermore, according to

Jin Wenda's 金文达 Fojiao Yinyue de

Chuanru Ji Qi Dui Zhongguo Yinyue de Yingxiang 佛教音乐的传入及其对中国音乐的影响 (The

Spread of

Buddhist Music and Its Influence on Chinese Music), the piece Puan Zhou is also found in the Beijing Zhi

Hua Si Shou Chao Pu 北京智化寺抄谱

(1694). It has a total of 18 sections. The subtitles are:

1.

Chui

Si Diao 垂丝调

2.

Fo

Tou 佛头

3.

Puan

Zhou – first section (Qi Duan 普庵咒起段)

4.

First

cycle (plus zhuan 1-3)

5.

Second

cycle (plus zhuan 1-3)

6.

Third

cycle (plus zhuan 1-3)

7.

Conclusion

jieduan 结段

8.

Jin

Zi Jing 金字经

9.

Wu

Sheng Fo 五声佛

This is a wind and

percussion (´吹打) ensemble piece; its title

and the division into sections is

identical to those of the string ensemble piece in Xian

Suo Bei Kao (see Table 2). I believe that there is a

direct

connection between these two pieces.

From Xian Suo Shisan Tao 弦索十三套,

the modern translation of Xian Suo Bei Kao,

it can be seen that apart from Chui

Si Diao at the beginning and Jin Zi

Jing and Wu Sheng Fo in the

finale, which are adapted from folk pieces (qupai 曲牌),

both the structure and the melody of

the main part this string ensemble

piece Puan Zhou are very similar to

the qin pieces Shi Tan Zhang and the

13 section version of Puan Zhou. The structures of

the three pieces are compared in

Table 2:

|

Shi Tan Zhang in

Qin Se He Pu |

Puan Zhou in Zhi

Hua Si Jing music and in Xian Su Bei Kao |

Puan Zhou in Zi

Yuan Tang Qinpu |

||

|

Fo Zhou Tou |

Chui Si Diao Fo Tou |

- |

||

|

Qi Zhou |

1st part 2nd part |

Puan Zhou section 1 1st cycle |

1st section |

1st part (without pal/dent.) 2nd part |

|

|

section 1 section 2 |

1st cycle 1st zhuan 1st cycle 2nd zhuan 1st cycle 3rd zhuan |

Section

2 |

|

|

1st cycle, section 6 |

2nd cycle |

Section

5 |

||

|

|

section 1 section 2 |

2nd cycle 1st zhuan 2nd cycle 2nd zhuan 2nd cycle 3rd zhuan |

Section

6 |

|

|

2nd cycle, section 6 |

3rd cycle |

Section 9 |

||

|

|

section 1 section 2 |

3rd cycle 1st zhuan 3rd cycle 2nd zhuan 3rd cycle 3rd zhuan |

Section

10 |

|

|

3rd cycle, section 6 |

Conclusion |

Section

13 |

||

|

Fo Zhou Tou |

Jin Zi Jing Wu Sheng Fo |

Coda in harmonics |

||

Table 2

There are two versions of Puan

Zhou in the Ju Shilin Pipapu. One is a short piece

(xiaoqu 小曲) of only 129

measures commonly known as Xiao Puan

Zhou 小普庵咒. This

is an abridged extract from the Puan Zhou in the Xian Suo

Bei Kao Pipapu. The other was handed down by Chen Mufu 陈牧夫 of

Zhejiang 浙江. It is 647 measures in length, divided

into 16 sections:

1.

Fo

Tou 佛头

2.

Qi Zhou 起咒

3.

Xiang Zan 香赞

4.

Lian Tai Xian Rui 莲台现瑞

5.

Zhan Tan Hai An 旃檀海岸

6.

Qi Zhou 起咒

7.

Fa Zan 法赞

8.

Yu Shan Fan Chang 鱼山梵唱

9.

Ri Ying Tan Hua 日映昙花

10.Qi Zhou 起咒

11.Bao Zan 宝赞

12.Zhong Sheng 钟声

13.Gu Sheng 鼓声

14.Zhong Gu 钟鼓

15.Ming Zhong He Gu 鸣钟和鼓

16.Qing Jiang Yin 清江引 (postlude)

The section titles of the pipa

piece Puan Zhou are elegant and scholarly, but are

not the same as those

of the qin piece and the piece from Xian

Suo Bei Kao. However the basic

structure and melody are similar to the qin

piece Shi Tan Zhang and the 13

section Puan Zhou.

The Present Day Puan Zhou

In Jue Yuan Qin Ji Xu 觉圆琴集序目

in the 1932 edition of Jinyu

Qinkan 今虞琴刊 it says of Puan Zhou that "This is a

Buddhist

piece. Two versions have been handed down in qin

handbooks. One has words, which are an incantation of the Chan

priest Puan. The other is without

words. It alone has the sound of bells and chimes, small cymbals and

singing in

praise. Listening to it is like hearing a

Buddhist song on Mount Yu 鱼山[2].

There are people now who play it." It is clear that the versions with

words are Shi Tan Zhang or are

similar to the 13 section version of Puan

Zhou. Versions without words are probably from the Beijing

Qinhui Pu 北京琴会谱 or a similar source.

The Beijing Qinhui

score solo

version as played by Pu Xuezhai 莆雪斋 is in Guqin Quji 古

琴曲集. The version he

recorded is identical to

that played and recorded by Wu Jinglue 吴景略 Zhang Ziqian 张子谦 and

others, and is the same as that which is played today. It must be true

that

"there are people now who play it".

The Beijing Qinhuipu

Puan Zhou is based on the 13 section

version of Puan Zhou, created by the

absorption of various techniques from folk instrumental music, such as

the

addition of beats, omission of notes, addition of ornamentation, rondo

techniques, etc. If we compare it with Shi

Tan Zhang, we find that several hetou 合头

are similar, whereas the other sections are very different.

However one

need only analyse them carefully and one can see that the one has

developed

from the other. It is as if the first two sections of the piece

developed from Qi Zhou extended by the addition of

ornamental notes and slowing down (ru

man 放慢)

(Example 5):

Example 5 Top:

Pu’an Zhou section 1, Bottom: Shitan Zhang

Qi Zhou

Sections 3 and 4 shown in

example 6 below are variations of hewei 合尾 phrases in all

18 sections in the

three cycles. The simple musical phrases in open notes are set off by

the ornamentation,

rondos and sections with the coordination of such fingering techniques

as jinfu 进复, dou 逗, zhuang

撞, etc.

It became the dominant musical section with a wide intervallic range (tiaofu 跳幅) and

intensified dynamics (lüdongxing

律动性). The

undulating, flowing rhythm of these two sections runs through the whole

piece,

and constitutes the main part.

Example 6 Hewei

phrase variations (Sections 3 and 4)

In the present-day Puan Zhou,

not only has the melody

changed greatly, but it also no longer has a structure consisting of 3

cycles

and 15 sections, or 3 cycles and 9 zhuan.

The 'cycles' are now in order of low pitch to high pitch, and are of

the new

form introduction – development – re-emergence. It omits the repeated

sections

and hetou phrases and phrases in

harmonics are inserted to add colour; prominent hewei

phrases either replace or reiterate and link together the

whole piece, making it a grave and solemn stanza.

If we compare it with

another modern handbook, Guqin Qu Huibian 古琴曲汇编, which

consists of scores of performances by Xia

Yifeng 夏一峰, we see that the melodic changes in Xia's score are

already the same as

present-day scores. The sections at the beginning and the two dominant hewei sections have already taken shape.

However, Xia's score preserves the overall arrangement into 3 cycles

and 9 zhuan. From this we can see traces of

the transition from the 13 section scores to the present day scores.

The new qin piece Puan Zhou has

already broken completely away from the qin

song with vocal accompaniment [style], and uses a new melody and a new

structure to depict the "bells and chimes, small cymbals and songs of

praise", and to hand down the artistic conception of the solemnity and

respect of Buddhism today.

Conclusion

To summarise the above, the

process of performance change from Shi

Tan Zhang to the present-day Puan

Zhou is already very clear. The sequence is shown in figure 1 below:

1592

1609

1802

1870

present day

San

Jiao Bo

Ya Zi Yuan

Qin Se

Rong

Size's qin

Tong ---->

Xin Fa –---> Tang

Qinpu ----------> He Pu –---> performance of

Sheng

qin song

Shi Tan Zhang

Shi Tan

Shi Tan Zhang

qin song Shi Tan

Zhang

Shi

Tan Zhang

----------------------

Zhang | |

|

|

|

|

|

Qin song Puan Zhou-------

|

(13 sections)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Qin piece

|

Puan Zhou

|

transmitted

by--

|

Xia

Yifeng |

|

|

|

|

|

Beijing

Qinhui Pu

|

Qin piece

|

Puan Zhou

|

|

|

|

1818

|

Hua Qiu Ping Pipapu

|------------------> Ju Shi Lin Pipapu ------> Solo pipa piece

|

Pipa

piece

Pua'an Zhou

|

Puan

Zhou

|

|

|

|

|

Xiao Puan Zhou

|

|

| 1694

1814

|

| Zhi

Hua Si Shou chaopu Xuan

Suo Bei Kao |

|----> Wind & percussion ------> String

ensemble -----

ensemble

piece

piece Puan Zhou

|

Puan Zhou

|

|

Folk ensemble piece

Puan

Zhou

Figure 1

From the scores, the structure

of the music and the melody, it can be seen that this piece of Buddhist

music

have first appeared as the qin song Shi

Tan Zhang. It was handed down from

the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty (end of the 16th century) to the present day, still retaining

the 21 section structure. At the hands of qin

players throughout history, it has changed from being a monotonous,

repetitive

piece of music for learning the pronunciation of repeated individual

Sanskrit

words to being an ancient and simple, solemn and respectful qin

piece.

After this Buddhist piece

appeared, it probably spread very widely; later, in order to further

popularise

it, and in particular to further religious activity, it was reduced to

the 13

section qin song Puan Zhou; it was

transferred from the qin to other folk instrumental

genres and became a wind and

percussion ensemble piece, a string ensemble piece and a solo pipa piece. Later, under the

counter-influence of folk instrumental music, the qin

song Puan Zhou

eventually became separated from the literary vocal accompaniment and

became

the present-day purely instrumental qin

piece.

References

1.

Qinqu

Jicheng 琴曲集成 vols. 7, 9,

edited by Wenhua-bu

Wenxue Yishu Yanjiuyuan, Yinyue

Yanjiusuo, Beijing Guqin Yanjiuhui 文化部文学艺术研究院,音乐研究所,北京古琴研究会,

published by Zhonghua Shuju Chuban 中华书局出版.

2.

Qin

Fu 琴府 Tong Kin

Woon (Tang Jianyuan) 唐健垣 ed.,

联贯出版社

3.

Puan

Chan Shi Quanji 普庵禅师全集 Wang Weishi 王微士,Zhou Xunnan 周勋男 ed.

4.

Qin

Shi Chubian 琴史初编,

Xu

Jian 许健 ed., Renmin Yinyue

Chubanshe 人民音乐出版社

5. Xian Suo Shisan Tao 弦索十三套, Cao Anhe 曹安和 ed., Renmin Yinyue Chubanshe 人民音乐出版社

6. Ju Shilin Pipapu 鞠士林琵琶谱 Lin Shicheng 林石城 ed. Renmin Yinyue Chubanshe 人民音乐出版社

7.

Guqin

Quji 古琴曲集 Zhongguo

Yishu Yanjiuyuan, Yinyue Yanjiusuo,

Beijing Guqin Yanjiuhui ed., Yinyue

Chubanshe 中国艺术研究院,音乐研究所,北京古琴研究会

8.

Guqin

Qu Huibian 古琴曲汇编 Yang

Yinliu 杨荫浏; Yinyue Chubanshe 音

乐出版社

9.

Fojiao

Yinyue de Chuanru Ji

Qi Dui Zhongguo Yinyue de Yingxiang 佛教音乐的传入及其对中国音乐的影响 (The

Spread of Buddhist

Music and Its

Influence on Chinese Music) Jin Wenda 金文达, in Zhongyang

Yinyue Xueyuan Xuebao 中央音乐学院学报 issue

1,

1992.

10.Folk Music of China, Stephen

Jones. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1998.

Glossary

an lü 按律

According

to the temperament???

an sheng 按声

According to

the sound???

dou 逗

Qin technique similar to zhuang

(q.v.) but slower

fang man 放慢

Slowing down

hewei 合尾 A phrase or variation similar to a refrain that is repeated at the

hui 回

Cycle

(movement?)

huixuan 回旋 Rondo?

yinqu 音区

Register

jia hua 加花

Ornamentation

jiezou 节奏

Tempo

jinfu 进复

Qin technique in which one slides to the

right and then returns

ju 句

Musical

phrase

lü dong 律

动

Dynamics

tian yan 添眼 Addition

of beats

tiaofu 跳幅

intervallic

range ?

xiaoqu 小曲

A

form of folk music structured into short, simple sections

yinqu

音区

Register

zhuan 转

A

group of sections